STUDY FINDS ASTHMA IN 25% OF CHILDREN IN CENTRAL HARLEM

New York – April 19, 2003 – A study has found that one of every four children in central Harlem has asthma, which is double the rate researchers expected to find and, experts say, is one of the highest rates ever documented for an American neighborhood.

Researchers say the figures, from an effort based at Harlem Hospital Center to test every child in a 24-block area, could indicate that the incidence of asthma is even higher in poor, urban areas than was previously believed.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has estimated that about 6 percent of all Americans have asthma; the rate is believed to have doubled since 1980, but no one knows why. New York City is thought to have a higher rate than other major cities, but that, too, is something of a mystery. The disease kills 5,000 people nationally each year.

Previous studies have pointed to rates above 10 percent, and as high as the high teens, in the South Bronx, Harlem and a few other New York City neighborhoods where a long list of environmental factors put people at higher risk. Several asthma researchers say they know of no well-documented level above 20 percent in the United States.

Related Article: EXPOSURE TO AIR POLLUTION AND COVID-19 MORTALITY IN THE UNITED STATES

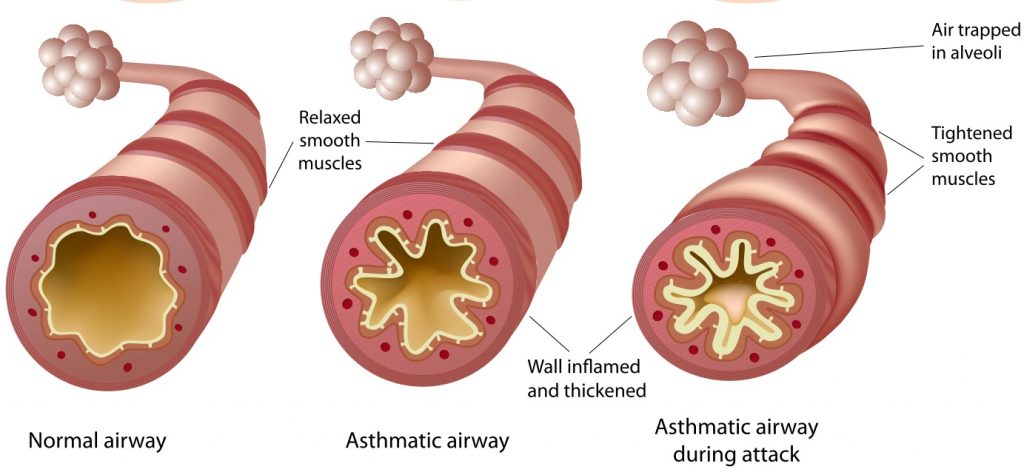

Asthma is an inflammation and constriction of the airways that makes it difficult to breathe. Scientists believe that only someone with a genetic predisposition can become asthmatic, but environmental factors like pollen, dust, animal dander, air pollution and cold air also contribute to development of the disease and can lead to attacks.

Some of the worst triggers, studies have found, are most prevalent in poor communities, including the feces of cockroaches and dust mites, cigarette smoke and mold and mildew. Harlem, East Harlem and the South Bronx also have a heavy concentration of diesel bus and truck traffic, and the tiny particles in diesel exhaust are thought to be another serious asthma trigger.

Most previous attempts to measure asthma were based on asking people whether they had ever received a diagnosis of the disease, or suffered from obvious symptoms of it. But a program begun last year tried something far more ambitious: to conduct asthma tests on every child under 13 who lives or goes to school in a 24-square-block area of central Harlem, more than 2,000 of them.

Nearly halfway through the screenings, the effort — by Harlem Hospital Center and Harlem Children’s Zone, a nonprofit group, with help from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, New York City and T. Berry Brazelton, the child development authority — has found that 25.5 percent of the children have asthma, including many who were not previously diagnosed.

The Harlem Hospital findings suggest that if blanket testing were more widespread, ”the rates might be much higher than suspected in any number of inner-city neighborhoods around the country,” said Dr. Stephen Nicholas, the head of the project, who is the director of pediatrics at Harlem Hospital Center and an associate professor at Columbia Medical School. ”We found that a lot of kids are floating through life without anyone knowing they have asthma.”

Related Article: REDUCING AIR POLLUTION EXPOSURE IN PASSENGER VEHICLES AND SCHOOL BUSES

”We know of a few other researchers doing similar studies in New York City that have not been released yet that have found similar rates,” said Mary E. Northridge, an associate professor at the Mailman school and editor in chief of the American Journal of Public Health. She helped set up the Harlem project’s questionnaire and is evaluating the resulting data.

”When I first met this group, I thought that they were nuts to think that they could test every child in an entire community, and then provide services to all of the ones who have asthma,” she said. ”It’s an enormous undertaking.”

Herman Mitchell, an epidemiologist who is a leader in asthma research coordinated by the National Institutes of Health, cautioned that studies could differ simply because there were problems in defining asthma and in making an accurate diagnosis.

Of the Harlem findings, he said: ”This is certainly one of the highest rates attributed in the United States, if not the highest. What they’re doing is quite exceptional in scope and it sounds like it’s good methodology, but until they publish and lay it out, it’s hard to judge.”

In many cases, the Harlem researchers said, children had obvious, longstanding signs of asthma but had never been diagnosed — either because the parents did not seek treatment or because doctors missed the signals. And in many other cases, they said, children whose parents reported no obvious signs of asthma turned out, on examination, to have mild cases of the disease, which can become more severe if left untreated.

”This is a very poor community where a lot of the families have very troubled lives, with lots of stresses, and that not only makes the problem more severe, it makes it much harder to even identify the problem and treat the problem,” said Geoffrey Canada, president of Harlem Children’s Zone.

Related Article: ADOPTING CLEAN FUELS AND TECHNOLOGIES ON SCHOOL BUSES: POLLUTION AND HEALTH IMPACTS IN CHILDREN

The finding of a high asthma rate is an accidental byproduct of an attempt not to measure the disease but to treat it. It grew out of the work of Harlem Children’s Zone, which was formerly known as the Rheedlen Centers. The group provides intensive, wide-ranging social services as disparate as training adults in parenting and helping people become homeowners, mostly in its self-declared zone, the area bounded by 116th Street, 123rd Street, Fifth Avenue and Eighth Avenue.

The group set out to address asthma, but first it wanted a sense of the problem’s scope. A preliminary survey of students at Public School 149 by the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene indicated an asthma rate of about one in five, higher than expected.

In 2001, Harlem Children’s Zone and Harlem Hospital joined forces, and the hospital won a grant from the Robin Hood Foundation to help the families of asthmatic children improve their medical care and living conditions.

Then, beginning last year, a team at the hospital set out to screen all of the roughly 2,200 children under 13 who live or attend school in the zone, asking about symptoms, listening to their lungs and measuring the rate at which they can exhale into a tube.

So far, the parents of 1,401 of the children have filled out questionnaires intended to detect possible signs of asthma, like nighttime coughing and wheezing, and 967 of the children have actually been examined. Nearly all of those tested so far are of school age, leaving out the younger children, in whom it can be hard to distinguish asthma from the respiratory ailments common to toddlers.

Related Article: NO BREATHING IN THE AISLES: DIESEL EXHAUST INSIDE SCHOOOL BUSES

The project staff aims to screen all the children by this summer and then to publish its findings.

One preliminary finding of the Harlem study is that children with asthma are about 50 percent more likely to live with someone who smokes than children who do not have the disease.

Another is that even parents who seek medical care often have a poor understanding of their children’s condition and treatment and do not give them medication properly. Yet another is that asthma is the leading cause of school absenteeism in the neighborhood.

Like the other work of the Harlem Children’s Zone, the goal of the asthma project is intensive intervention. Doctors, nurses, social workers and others repeatedly visit the families of asthmatic children over many months, and, among other steps, help them get holes in walls and broken windows repaired, in some cases help them replace dust-loaded furniture and carpets, teach them to clean and provide cleaning materials, go on doctors’ visits with them and oversee the taking of medicine.

This ARTICLE was written by Richard Pérez-Peña and published in The New York Times, Section A, Page 1 of the National edition with the headline: Study Finds Asthma In 25% of Children In Central Harlem on April 19, 2003.